CO2 emissions from the building sector A reckoning is (fast) approaching

Jens Hirsch, Domain Expert Sustainability at BuildingMinds

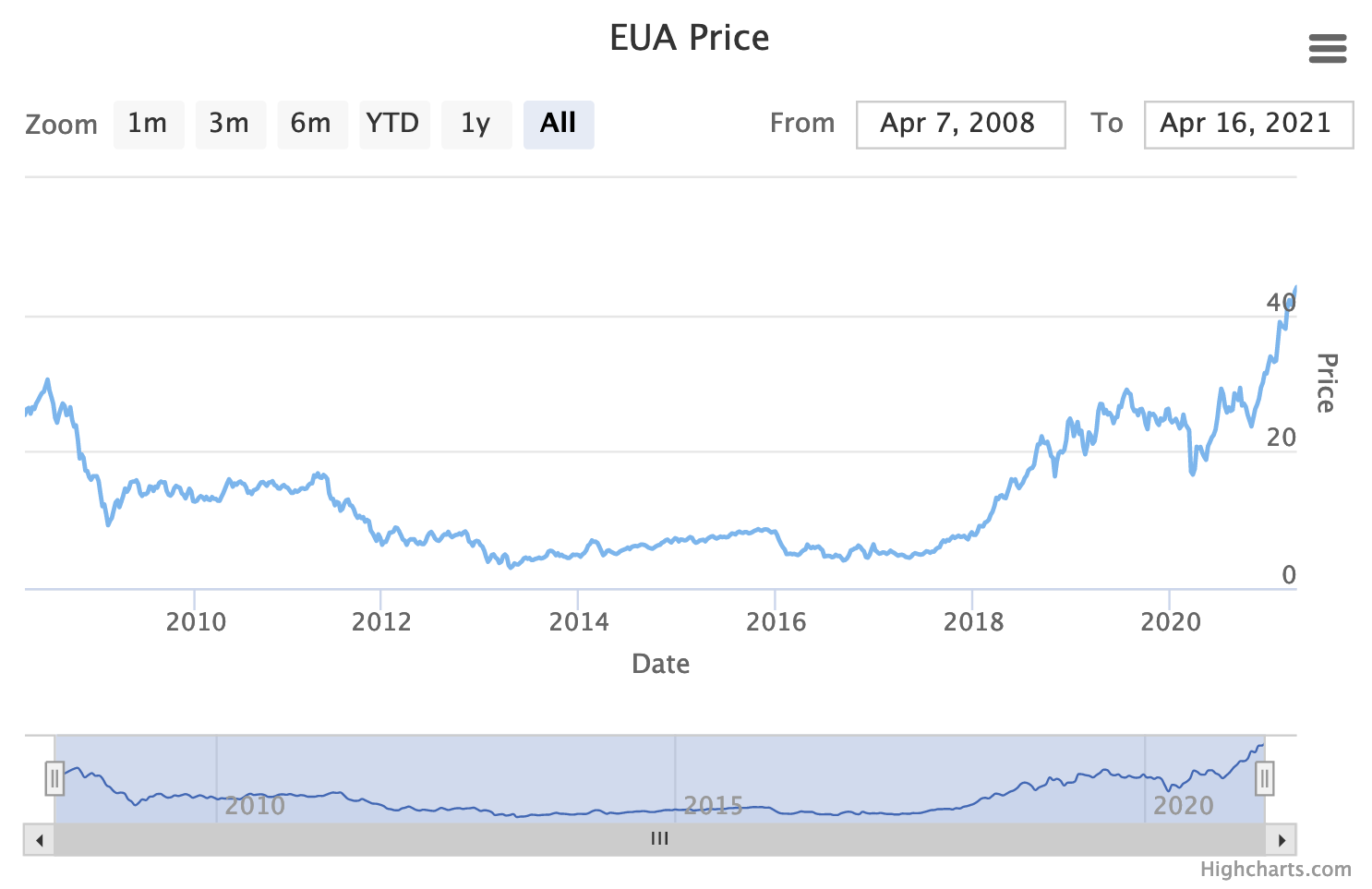

After more than a decade of blaming the EU Emissions Trading System for its ineffectiveness due to carbon prices far too low to impose any effect, we recently witnessed an unprecedented rally to more than 40 € per ton. Over the next few years, many buildings are set to become huge cost burdens as “stranded assets”. Why? Well, because of the future price regime for CO2 emissions. A relatively simple calculation reveals the potentially significant financial fallout investors and corporates face if they fail to take their environmental responsibilities seriously.

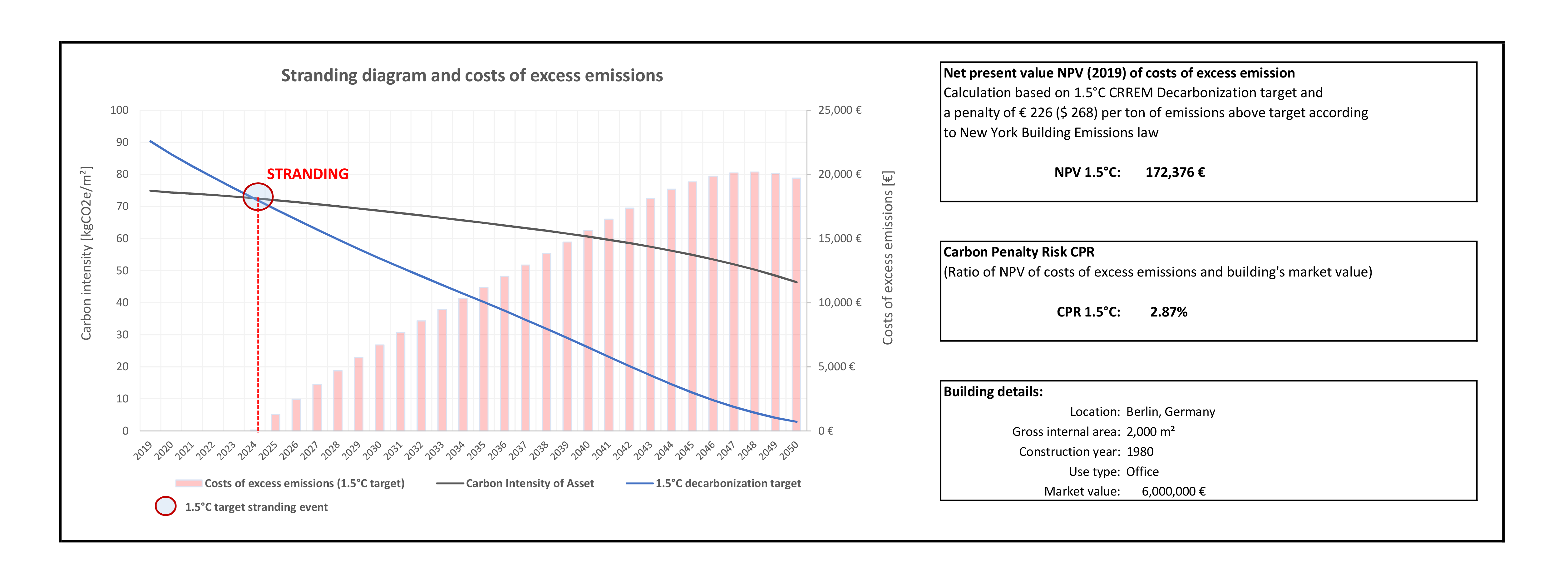

Take an office property in Berlin, built in 1980 with a gross floor area of 2,000 square metres. Based on this building’s Paris-aligned CRREM 1.5°C decarbonisation pathway (see below), we calculated the net-present value of potential future carbon costs for this building until 2050. The applied monetary penalty of $ 268 per ton of carbon emissions exceeding the decarbonisation target is based on the recently enacted New York Climate Mobilization Act. This “climate change penalty” corresponds to just under 2.9 per cent of the market value (EUR 6 million) of the property unless adequate decarbonisation measures are implemented to reduce or avoid emission penalties. Even if you only apply the rather low taxation on fossil fuel emissions set out in the German Fuel Emissions Trading Act, the building still faces additional costs of around 1.1 per cent of its market value. Such value adjustments represent the down-side risk of climate change and the transition towards a low-carbon economy. Applying intelligent retrofit measures does not only allow asset owners to avoid such carbon penalty costs, but also reduces the dependency on volatile energy prices, finally resulting in more attractive and valuable buildings.

CRREM provides clarity

Our sample calculation above is based on findings and benchmarks from the Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor project (CRREM for short), which is supported by the European Union (EU) and a consortium of leading real estate investors, industry bodies and academia. Taking empirical data on the maximum available global emissions budget that is compatible with the Paris climate goals, the CRREM project for the first time developed national and segmental decarbonisation pathways to enable the real estate industry to identify and quantify transitional climate risks (“carbon risks”) and take appropriate action to mitigate them. As a reminder: According to the World Green Building Council, if we want to to comply with the Paris Climate Agreement and limit global warming to well below 2.0°C (ideally 1.5°C) compared to pre-industrial levels, every building will need to be CO2-neutral by 2050. The EU and its member states are pushing this goal by introducing a raft of new regulations such as the latest “2030 Climate Target Plan”. The EU Commission announced that the concept of emission trading will be extended to further sectors including real estate. Putting a price on CO2 is only one of many measure aiming to meet the EU’s ambitious climate targets, but the above sample calculation clearly demonstrates that companies in the real estate industry can no longer ignore carbon risk.

The “stranding moment” is no more than a few years away

Reducing CO2 emissions from existing buildings requires investment – and it needs to happen quickly. Without action and depending on the applied global warming target , the Berlin office building cited above is at risk of missing it decarbonization targets as early as 2024 – unless suitable countermeasures are implemented. Thanks to the transparency that comes along with the increasing adoption of the CRREM framework within the industry and especially among long-term focussed investors such as pension funds, this stranding risk is anticipated and factored into valuation already now. . If we assume a decarbonisation target of 2.0°C, the stranding moment will not occur until 2030. But even in this case, the costs of the building’s excess emissions would still be enormous: the net present value of the costs of the property’s excess emissions (above target) would still total almost 1.7 per cent of its market value.

Increase transparency or pay the price

Asset managers and corporates simply cannot afford costs on this scale. There is a window of opportunity to minimise the financial fallout – but it is closing fast and action is required. Crucially, real estate owners and operators need transparency. They first need to determine the extent of the emissions from their individual properties and entire portfolios if they are to have any basis for meaningful action at all.

This is where data play a key role. In order to generate actionable insights, you need structured and systematised data. And these date must not be limited to individual buildings. Investors, asset managers and corporates generally own or manage a number of properties, so they need a portfolio-level perspective. They also have to deal with large volumes of data from disparate data sources, systems and standards. Current methods and tools either tend to represent isolated, stand-alone solutions or are fast approaching the limits of their capabilities. As far as BuildingMinds is concerned, the real estate industry needs a single platform and Common Data Model to tap the potential of data, because it is only through data standardisation and harmonisation that we can master the increasing complexity of real estate and portfolio management. In particular, this also applies to the development and implementation of decarbonisation strategies. Moreover, the sustainable management of real estate doesn’t just reduce risks and mitigate the threat of upcoming emissions levies or the even more punitive penalties for greenhouse gas emissions coming our way in the very near future. It also represents a pathway to asset optimisation and, when done right, can even increase the profitability of your real estate investments.