Risk or opportunity? A smart digest on stranding asset prevention for insurance.

Reading time 12 minutes - enjoy the read!

Manuel Holzhauer, Insurance Industry Executive at Microsoft Germany, and Dr. Jens Hirsch, Head of Sustainability & Scientific Research at BuildingMinds

What do the insurance industry and 100-yard-dash sprinters have in common? Well, both are focused on a clearly defined goal. Sprinters repeatedly measure and fine-tune every minute detail of their performance in order to optimize it for a decisive race. The insurance industry, on the other hand, is currently running briskly towards its sustainability goals, but largely without interim measurements and thus without orientation – which could be its undoing, given the ambitious scale of this undertaking.

Sustainability – often referred to as ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) – increasingly determines how insurers act. As with other industries, insurers are currently primarily focused on the E, the environmental aspects, and in particular on carbon dioxide emissions. According to the Dutch environmental agency PBL, global greenhouse gas emissions before the coronavirus pandemic amounted to around 52 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent. And the building sector deserves special attention: Although buildings are responsible for only about 30% of overall energy consumption, they produce around 40% of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions.

Affected on many levels

For insurers, climate change, due largely to CO2 emissions that have increased over decades, poses complex challenges. Consequently, it is essential to focus on reducing carbon dioxide emissions. However, if you look at the ways climate change affects the insurance industry when it comes to real estate, it quickly becomes apparent that focusing on emissions alone is not enough. Whether it is operations in owner-occupied real estate, real estate portfolios held as investment assets, or the underwriting side of the business – the consequences of climate change emerge in different ways. They are both regulatory and physical, as was made clear not least by the disastrous floods in Germany in recent years, as well as other devastating natural catastrophes around the world in 2021. Munich Re assesses global losses from natural catastrophes at US$280 billion, of which less than half were insured.

When it comes to possible strategies and measures for assessing and minimizing climate risks, real estate investments are an obvious choice, as they are subject to both physical and transitory risks. From both perspectives, reducing CO2 emissions is essential – and not only because the German Insurance Association (GDV) has proclaimed the goal of climate neutrality for German insurers’ own business processes by 2025 and for their investments by 2050. Moreover, many insurers have committed themselves to sustainable investment strategies, and many have signed up to the UN Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance and/or the UN Net-Zero Insurance Alliance. The industry, which is more dependent on the trust of its customers than almost any other, must therefore act if it does not want to be accused of not living up to its responsibility and commitment – or worse: of greenwashing. Because simply erecting a beehive on the building’s roof, or planting young trees, is no longer good enough. The measures that are implemented must do much more. On top of that – and this is crucial – their success must be verifiable.

Reputational risks due to lack of data (transparency)

However, there is an enormous gap between this realization and targeted action, which becomes apparent in the lack of reliable data. What emissions are generated by insurers’ real estate investment assets, or even by the buildings insurers themselves occupy? Where does the data come from, and does it adequately reflect the current situation and future risks? What can be derived from the data – not only with regard to the management of real estate portfolios, but also, for example, the design of insurance products? In specific terms: Is it possible to make a data-based and thus valid prediction of the impact that a switch from oil or gas to renewable energies would have – across an entire portfolio? Many of these questions are still unanswered. While insurers do collect data, data collection must not be an end in itself. Both too little data and inaccurate data mean that, on the one hand, risks cannot be adequately assessed, managed, or insured, and on the other, that entrepreneurial decisions cannot be credibly justified.

A specific example: In 2021, it was announced that Axa would no longer be able to provide insurance cover to RWE. Axa explained its decision by pointing to the energy company’s focus on fossil fuels. Axa’s decision to withdraw its services not only affects RWE’s coal-fired power plants, but all segments of the company that need to be insured, from employees to transport to real estate and operations. This is not only a problem for RWE and other companies that may be affected in the future, it also puts other insurers under pressure – or at the very least they will have to defend their own decision-making processes, because they will need to explain why their underwriting guidelines, unlike Axa’s, allow them to offer insurance cover. Conversely, the question arises as to whether the insurance industry might not contribute much more to the fight against climate change by, for example, providing its customers with higher levels of cover if they use green energy or take technological advice from risk engineers.

Hurdle race: data collection and analysis

Essentially, if companies want to be able to assess which response and measures make most sense, they need a resilient and objective basis for their decisions – which only data can provide. This also and especially applies to real estate investment assets. However, many hurdles already lurk when collecting data: Owner-occupied and investment portfolios are regionally diversified, as are insured assets. Country units and departments work with different systems that are not always compatible. Data comes from different sources and is therefore not directly comparable. This has its origins not least in the highly fragmented real estate industry. Once the data – currently mostly fragmented, difficult to process and consequently potentially error-prone – has been brought together, the question arises: How can the data be analysed and what conclusions can be drawn from it? For example, can analysing the data help identify targeted measures to reduce the CO2 emissions of a building or an entire real estate portfolio with a limited budget and by a defined target date? Does the data allow constant comparison and benchmarking throughout the entire process? The list of challenges could be expanded indefinitely.

The holistic view of real estate

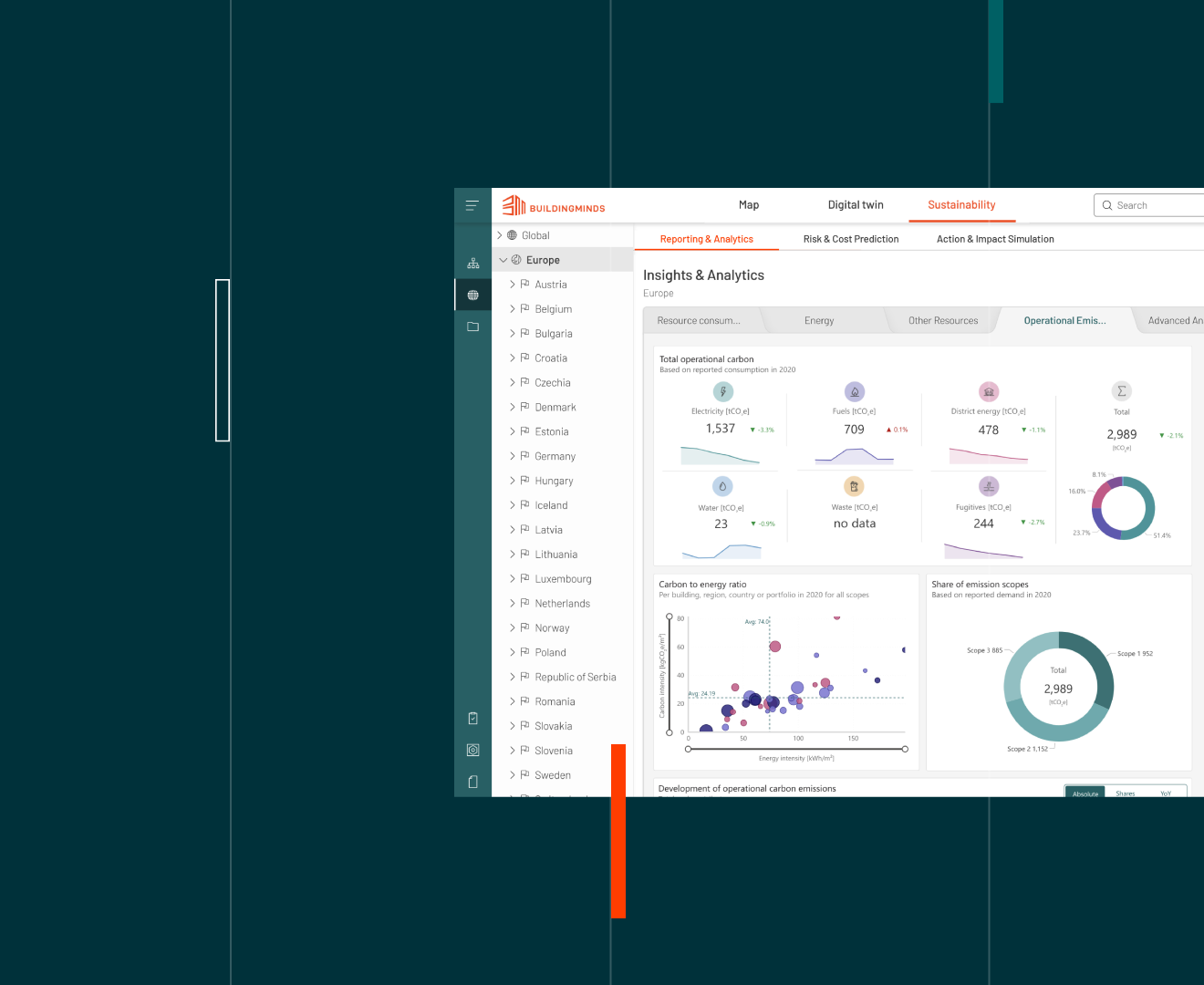

In view of this complexity, the solution must consist of a variety of elements. For one thing, a data platform is needed in which all of the information comes together. For each building, this is best illustrated by a virtual image – a digital building twin – which contains all of the data from the building (including energy consumption and associated emissions). In combination with other analyses and sources, the digital twin allows meaningful conclusions to be drawn about physical climate risks. It can also map details relevant to insurance in the narrower sense, such as technical building infrastructure, including smoke detectors and sprinkler systems. Taken together, several such digital twins can be combined to provide a portfolio-level view.

A common data language is needed to enable data from different sources and systems to be processed on a single platform. The real estate industry is currently working on the Common Data Model – which is already established in other sectors – in the form of the IBPDI initiative.

Once the data has been compiled and harmonised on the platform, the real work begins: Developing scenarios and identifying suitable measures to bring the portfolio closer to the declared decarbonization goal in a coordinated, economically feasible manner. It is also important to check the outcomes and, where necessary, adjust the planned retrofit measures.

Recognising the stranded asset moment – and reacting appropriately

The decarbonization of an investment portfolio is a basic prerequisite for sustainable business growth and boils down to a single question: When does a building become a stranded asset that no longer meets regulatory requirements or the expectations of the real estate market? From this set of tools and knowledge, insurance companies can and must make the connection to their product portfolios, because one question comes to the fore: Can a stranded asset actually be insured?

One thing is certain: Insurers have enormous power – and with it, responsibility. Companies are dependent on insurance coverage, and real estate plays an enormous role not only as a key element of entrepreneurial activity, but also in the fight against climate change. Digitalization is the key – and extends far beyond the ESG use case, by the way. The impact of digitalization could change, if not optimize, the entire value chain of the insurance industry. Those who fail to recognize this in their own portfolio and at the product level, or who act too late, risk damaging their reputation, because in addition to legislators, both customers and employees are increasingly setting higher standards – including efficient, digital processes and sustainability – when it comes to choosing service providers and employers. At the same time, companies from outside the sector could close the gap and become serious competitors. It would not be the first time that this has happened to an industry. Conversely, in the best case, a new market could open up for the first movers.

Manuel Holzhauser - Insurance Industry Executive at Microsoft Germany

Manuel Holzhauser is Insurance Industry Executive at Microsoft. Previously he worked in management positions for numerous well-known companies and organizations including Pricewaterhouse Coopers, Accenture, Munich Re and the Insurtech Hub Munich. He holds extensive, in-depth expertise in the startup, finance and insurance industry.

Dr. Jens Hirsch - Head of Sustainability & Scientific Research at BuildingMinds

Dr. Jens Hirsch is Head of Sustainability & Scientific Research at BuildingMinds and substantially responsible for the development of integrated decarbonization and digitalization strategies for real estate portfolios. Before he joined BuildingMinds, Jens lead the EU research project “CRREM Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor,” which translates required emission targets of the Paris Agreement into concrete decarbonization pathways for real estate.

Bibliography, info and FAQs from